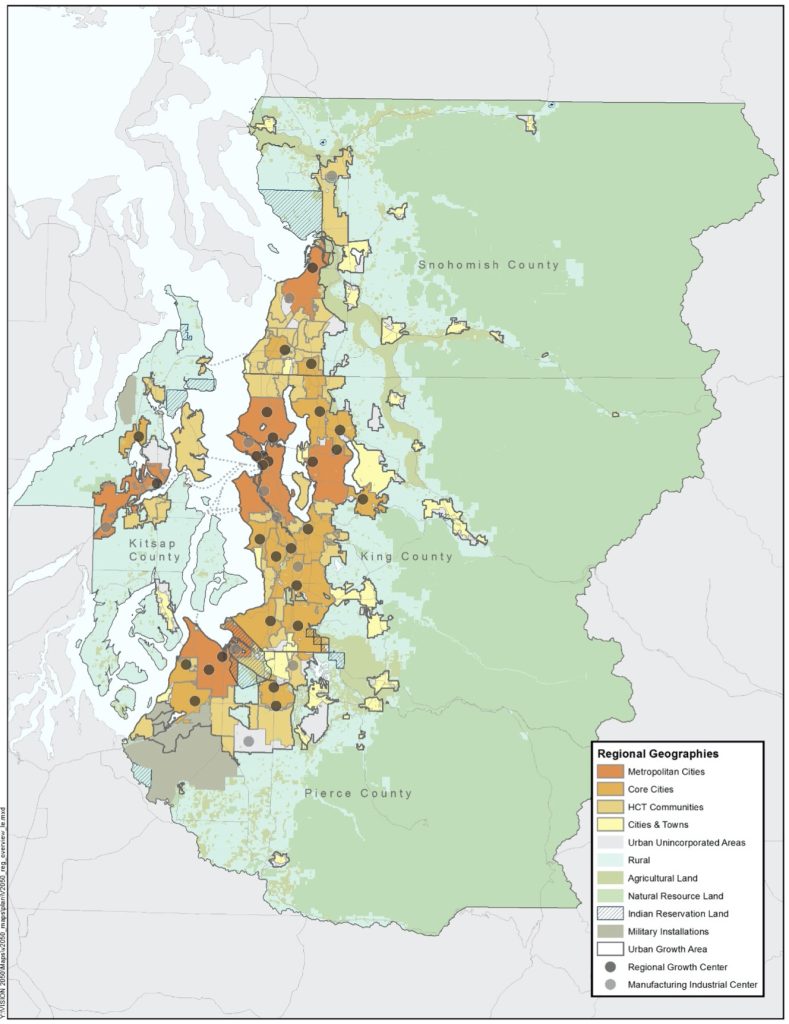

On Friday, the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC) adopted Vision 2050, the blueprint for growth and transportation investments in the four county region. As King, Kitsap, Pierce, and Snohomish Counties are projected to add a combined 1.8 million people over the next 30 years, the document will guide investments in infrastructure and focus growth.

With the four counties, Vision 2050 and PSRC cover the transportation and planning projections for 76 cities and towns, four tribes, six transit agencies, five ports, two universities, and an assortment state and regional transportation and transit agencies. It’s an exercise in regionalism that can result in broad objectives and narrow impacts.

More specifically, Vision 2050 sets the template for the next wave of local planning documents. Counties and cities throughout the region will be updating their comprehensive plans in 2024. PSRC will review each plan for conformance with the Vision 2050 targets. For that reason, Bruce Dammeier, Pierce County Executive and PSRC General Assembly President, called Vision 2050 the “Hallmark document that will guide our planing process for the next 10 years.”

For its flaws, and we’ll get to them, Vision 2050 is a well written and thoughtful planning document. It provides strong framework for the Puget Sound region to responsibly and sustainably grow into the next 30 years. Since its last incarnation as Vision 2040, policies were added to address equity and climate change. New targets have been added to focus development around transportation hubs. Restrictions on development outside the growth area are provided with workable tools.

Vision 2050 is the broadest view of planning in the Puget Sound Region. The generalized dots of growth and industrial centers, the aspirational statements of purpose, and the lack of municipal boundaries all combine to show the widest picture of life and development in the four-county area. That vision is then colored with a variety of maps and very lovely illustrations.

The plan isn’t just pretty. It has teeth guaranteed in state law. The Growth Management Act (GMA) requires all local plans to conform with the regional growth targets. If the GMA is a machine that lets communities build local comprehensive plans, Vision 2050 is the pattern for those plans around Puget Sound.

Between statutory effectiveness and being really well constructed, Vision 2050 is likely one of the premier regional planning documents in the country. Regional planning in the United States is often a non-starter due to the country’s pathological fixation with home-rule. Most regional groups are single purpose entities that run the water district or the airports, or a regional cooperative that does a lot of marketing and nice lunches. Puget Sound Regional Council has a purpose, a direction, and authority to make it happen.

However, Vision 2050 is inherently an update to its predecessor, Vision 2040. While it finds many new topics to explore, it is still fundamentally based on a suburban model that has not kept pace with the last decade of growth. There is a lot of discussion of compact urban communities, but not the awkward adolescence of getting there.

For example, Vision 2050 includes policies that promote increased urban tree coverage. Opponents to bike lanes and building complete streets can argue that removing street trees violates that policy. We saw this in giant frontpage type with The Seattle Times’ April 15, 2019 headline “Thousands of trees will be removed to make way for Light Rail to Lynwood.” Yes, and it’s going to be okay.

The term “character” appears in the document 12 times, each of which can be used as an argument against reasonable projects that simply look different that what exists right now. Anti-density and anti-affordable housing lawsuits cite aspirational environmental and community policies to delay and defeat housing and infrastructure projects.

Of course, Vision 2050 is a regional planning document and these policies must be implemented by local comprehensive plans. That’s why completing Vision 2050 this year is important. Localities can have the pattern ready for 2024, when the next comp plans are due.

But it also means that the implementation of this premier regional planning document is in the hands of 104 different agencies and jurisdictions. We have to rely on our fractured, patchwork of municipalities to take a regional view. Communities like Clyde Hill, Hunts Point, Yarrow Point, and Medina are allowed to get all the benefits of their local affiliation with neighboring Bellevue and easy access to regional infrastructure, but get to be treated like remote towns and cities. These areas are expected to take up 6% of the region’s population growth and 4% of its employment growth over the next 30 years.

On the other hand, unincorporated and underrepresented areas like White Center and Skyway are shuffled into “High Capacity Transit Communities” akin to Shoreline or Mercer Island that are imminently served by light rail. These regions are expected to take 24% of the region’s population growth and 13% of its employment. The document mentions “displacement” 20 times, but do not talk about it specifically for unincorporated areas. Though predominantly Black, Indigenous people of color (BIPOC), both neighborhoods are rated the same displacement risk as Interbay and Ballard.

Friday’s PSRC General Assembly vote was the final step in a series of meetings to approve Vision 2050, all of which were delayed due to Covid. Originally scheduled for May, the process stalled as PSRC committees worked to comply with the Governor’s Stay Home Stay Healthy orders and elected officials who comprise those committee members were faced with urgent matters and budgets in their home jurisdictions.

Vision 2050 was reviewed and vetted by dozens of boards and committees over the last three years as the PSRC staff and regional leaders reached out for community comment. There were rounds of public input and response to the draft plan. These were heard through PSRC’s Growth Management Policy Board who sent the draft up to PSRC’s Executive Board who in turn recommended approval to the PSRC General Assembly. It is the very definition of austere planning, one that represents a layered resistance to change.

In introducing the motion to adopt Vision 2050, chair of the Growth Management Policy Board and Everett Councilmember Scott Bader said: “We had some debates along the way and some challenging issues.”

The most challenging recent issue involved the growth target for rural Snohomish County. The county would like a higher allowance for growth permitted outside its growth boundary. While their motion was narrowly defeated in earlier committees, County Executive Dave Somers proposed a final amendment to raise the allowable number of homes by about 5,500 units over 10 years.

His argument is straightforward. Snohomish County’s rural growth was 20%, lowered to 10% in Vision 2040. They achieved this target. But it was again lowered to 3% in Vision 2050 which they believe is unattainable. So Snohomish proposed to allow a growth target of 4.5% in its rural areas. “We need to be able to keep our commitments and be realistic about it. From a planning perspective it’s very important to us,” County Executive Somers said.

Representatives of other counties and jurisdictions spoke for and against the amendment. King County Executive Dow Constantine reviewed his earlier opposition to the proposal, but signaled support due to the addition of other language. Mayor Becky Erickson of Poulsbo also spoke in support, focusing on being realistic about infrastructure and not underbuilding in places that need new roads.

Roger Millar, Secretary of Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT), had some direct answers about rural roads. He listed the holes in the budget. “$3.1 billion fish passage obligation. We have a $1.5 billion unmet seismic retrofit requirement. Over the next 10 years, statewide we have a $7 billion shortfall in our State of Good Repair investment.” He then focused on what that means for roads going to these new houses. “We do not have the resources as a state to address the commitments in place or complete actions in a timely manner. Your friendly neighborhood DOT cannot accommodate rural growth at 3%, 6% the money is not there.”

This was echoed by Duvall Mayor Amy Ockerlander, opposing the amendment. “We don’t have a way to connect our transportation systems from where people are living to where they are working.” The Mayor described traffic moving through downtown Duvall to unfunded county roads.

In the end, the amendment passed, as did the Vision 2050 plan as a whole. PSRC’s system of weighted voting is based on population. With the four counties and Seattle voting for the amendment and final plan, there was little doubt. Most of the remaining cities and towns voted for them too.

That tension is striking. PSRC is set up well, primed for forward-looking change. They develop quality plans and research like Vision 2050.

At the same time, the barriers to change are high and to participation are higher. To play in this field, you have to be an elected official. Yes, there are a lot of towns and cities in the Puget Sound region, but many are set up to exclude people that are not White homeowners. After years of developing the plan, Snohomish County got its way for growth in unincorporated rural areas in a last round amendment. But unincorporated urban King County barely had a seat at the table.

Fortunately, a new table is getting set up. Lots of them. Futurewise is preparing amendments to the Growth Management Act for the 2021 Washington Legislative session. They’re looking to strengthen GMA implementation for racial equity and housing and climate change. Communities are educating neighbors ahead of their town’s comp plan updates. Community groups are pushing back on short-term plans that jump the start on the upcoming comp plan process.

As Pierce County Executive Dammeier put it “It’s important to note that the successful planning of this region does not stop with the General Assembly. In fact [today’s vote] is the conclusion of a big effort, but the start of an even more significant effort as all of us work to implement the regional planning policies as we go forward. So there’s still a lot of work ahead of us.”

We’re done visioning 2050. Now it’s time to prepare for 2024.