Tomorrow marks the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, which was passed by Congress on October 18, 1972—establishing a nationwide approach to improving the quality of our nation’s lakes, rivers, streams, and other water bodies. Over the last 50 years, the health of our waters has improved, but threats to water safety remain.

Today’s WatchBlog post looks at our work on key federal programs for ensuring compliance with and enforcement of the Clean Water Act (Act).

What does the Clean Water Act require?

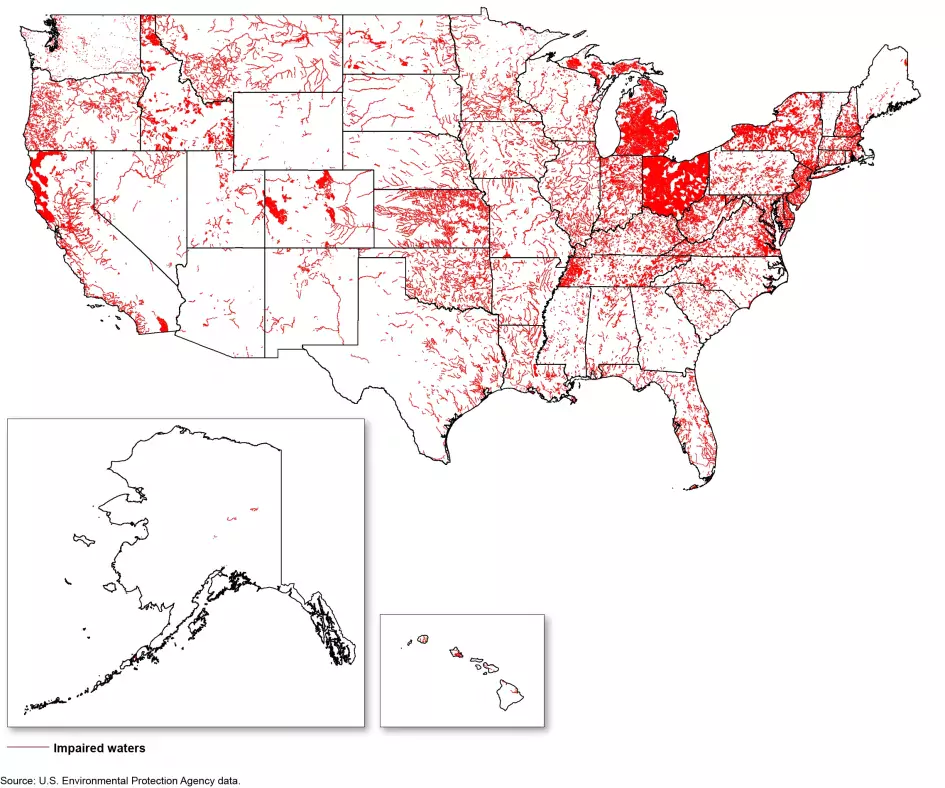

The Act requires the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—along with states, tribes, and territories—to monitor the quality of U.S. lakes, rivers, streams, estuaries, and other water bodies. EPA and states are also required to list water bodies that are impaired by pollutants and to plan for cleaning them up. Yet, EPA’s most recent report (from 2017) says that only about half of U.S. waters have been assessed to date, meaning that quality of the other half has not been assessed and their status is unknown. This has changed little since our 2013 review found the same.

Most Recent Map of Impaired Waters (As of 2015)

as of 2015" width="709" height="591" />

as of 2015" width="709" height="591" />

Limited monitoring makes it difficult to detect and warn of harmful substances in water bodies. For example, we recently reported that limited monitoring for harmful algal blooms in fresh water, may hamper efforts to identify the risks blooms could pose to human health and aquatic life. All 50 states have experienced harmful algal blooms and, according to federal agencies, may experience more blooms in the future with climate change and warming waters.

What are the sources of pollution in our waters?

One key program under the Act established requirements for regulating and limiting point sources of pollution—pollution that is discharged into waters from sources such as pipes from industrial facilities and wastewater treatment plants.

This type of pollution is allowed, but requires permits. Permit holders must self-report discharges and noncompliance with water quality requirements. In 2021, we found that EPA lacks reliable information needed to ensure polluters are complying with their permits. We also recommended steps to improve that will help EPA identify and reduce illegal discharges.

While point source pollution is an important issue, the leading cause of water pollution is nonpoint sources. These sources come from runoff that carries sediment, oil, bacteria, toxins, and other pollutants from farms, yards, and paved areas (e.g., streets and parking lots) into nearby waters. Such pollution can harm fish and other aquatic life, lead to the development of harmful algal blooms, and contribute to ocean acidification in coastal waters, an emerging threat to marine life on which we previously reported.

EPA funds projects to protect watersheds and reduce the types and amounts of pollutants in runoff. Earlier this year, we found that EPA needed to take stronger actions to address these nonpoint sources of pollution, such as issuing new regulations. This would improve EPA’s ability to protect our nation’s waters. We also think action from Congress is needed to better manage nonpoint source pollution. This might entail strengthening the approach to funding watershed protection projects in the Clean Water Act or removing impediments to treating polluted runoff.

The graphic below shows examples of how pollutants from both point sources and nonpoint sources enter our waters.

What are the emerging threats to our waters?

Recently, the discovery of widespread pollution of rivers, lakes, and groundwater by persistent chemicals called PFAS, has raised concerns about the risks to human health. PFAS are commonly used in consumer goods, such as nonstick pans, food packaging, and carpeting. They are considered “forever” chemicals because they don’t break down in the environment and can accumulate in our bodies. In 2021, we reported on EPA’s attention to PFAS, including its efforts to identify and control industrial sources of them. In April 2022, EPA announced actions to protect communities and the environment from PFAS. These measures include using the Act’s permitting authorities to reduce PFAS discharges, obtaining monitoring information on PFAS sources and quantities, and using the data for EPA decisions about restricting releases of PFAS by industrial facilities and others.

Other recent events, including Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico and Hurricane Ian in Florida, as well as the flooding in Jackson, Mississippi, have caused water and wastewater infrastructure to fail—leaving people without water and sewer service. We reported that disasters are expected to increase with a changing climate and will cause increased damage and more failures. EPA can provide technical assistance to help water utilities prepare for future climate change impacts. We also recommended that Congress ensure that the funding it provides for water infrastructure improves resilience.

Where do we go from here?

Before the passage of the Clean Water Act, large numbers of our nation’s lakes, rivers, and streams, were polluted with raw sewage, industrial chemicals, and dangerous metals. For example, here in Washington, D.C., the Potomac River was so polluted with sewage that the smell across parts of the National Mall was nearly unbearable. The Cuyahoga River in Ohio was so polluted with oil and debris that it used to catch on fire!

While the sources of pollution that created such situations have largely been addressed, threats from more dispersed sources—such as stormwater runoff that carries pollutants into our waters—will require further actions. Emerging threats resulting from a changing climate also need to be addressed. The key to tackling these threats will require using the tools provided by the Clean Water Act. But more action may be needed to strengthen the Act and help it meet the goals established half a century ago.

To learn more, you can see our body of work on clean water here.